When Was The Camera Made

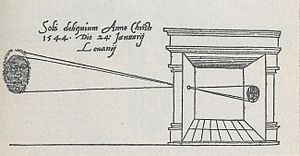

First published picture of a camera obscura in Gemma Frisius' 1545 book De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica

The history of the camera began fifty-fifty before the introduction of photography. Cameras evolved from the photographic camera obscura through many generations of photographic applied science – daguerreotypes, calotypes, dry plates, film – to the modern day with digital cameras and camera phones.

Camera obscura (11th–17th centuries) [edit]

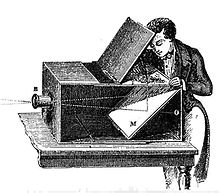

An artist using an 18th-century camera obscura to trace an image

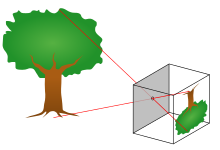

The forerunner to the photographic camera was the camera obscura. Camera obscura (Latin for "night room") is the natural optical phenomenon that occurs when an image of a scene at the other side of a screen (or for instance a wall) is projected through a modest hole in that screen and forms an inverted image (left to right and upside downwards) on a surface contrary to the opening. The oldest known record of this principle is a description past Han Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 to c. 391 BC). Mozi correctly asserted that the camera obscura image is inverted because light travels in direct lines from its source. In the 11th century, Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) wrote very influential books about eyes, including experiments with lite through a small opening in a darkened room.

The employ of a lens in the opening of a wall or closed window shutter of a darkened room to project images used as a drawing aid has been traced dorsum to circa 1550. Since the late 17th-century portable camera obscura devices in tents and boxes were used as a drawing assist.

Before the invention of photographic processes, there was no manner to preserve the images produced past these cameras apart from manually tracing them. The earliest cameras were room-sized, with space for 1 or more people inside; these gradually evolved into more and more compact models. By Niépce's time, portable box camera obscurae suitable for photography were readily available. The first camera that was small and portable enough to be applied for photography was envisioned past Johann Zahn in 1685, though it would be well-nigh 150 years before such an application was possible.

Pinhole camera. Light enters a dark box through a modest hole and creates an inverted epitome on the wall opposite the hole.[1]

Ibn al-Haytham (c. 965–1040 Advertising), an Arab physicist also known as Alhazen, wrote very influential essays almost the photographic camera obscura, including experiments with light through a small opening in a darkened room.[2] The invention of the camera has been traced back to the work of Ibn al-Haytham,[iii] who is credited with the invention of the pinhole camera.[4] While the effects of a single low-cal passing through a pinhole had been described before,[three] Ibn al-Haytham gave the offset correct analysis of the photographic camera obscura,[5] including the showtime geometrical and quantitative descriptions of the phenomenon,[6] and was the beginning to use a screen in a dark room and then that an image from one side of a hole in the surface could be projected onto a screen on the other side.[7] He besides starting time understood the human relationship between the focal bespeak and the pinhole,[8] and performed early experiments with afterimage.

Ibn al-Haytam's writings on optics became very influential in Europe through Latin translations, inspiring people such equally Witelo, John Peckham, Roger Bacon, Leonardo da Vinci, René Descartes and Johannes Kepler.[2] Photographic camera Obscura were used as drawing aids since at least circa 1550. Since the tardily 17th century, portable camera obscura devices in tents and boxes were used every bit cartoon aids.[ citation needed ]

Early on photographic camera (18th–19th centuries) [edit]

Before the development of the photographic camera, it had been known for hundreds of years that some substances, such as silverish salts, darkened when exposed to sunlight.[9] : 4 In a series of experiments, published in 1727, the High german scientist Johann Heinrich Schulze demonstrated that the darkening of the salts was due to light lonely, and not influenced by heat or exposure to air.[10] : 7 The Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele showed in 1777 that silver chloride was specially susceptible to concealment from low-cal exposure, and that once darkened, information technology becomes insoluble in an ammonia solution.[10] The offset person to use this chemistry to create images was Thomas Wedgwood.[ix] To create images, Wedgwood placed items, such as leaves and insect wings, on ceramic pots coated with silver nitrate, and exposed the gear up-up to low-cal. These images weren't permanent, nonetheless, as Wedgwood didn't employ a fixing mechanism. He ultimately failed at his goal of using the process to create fixed images created by a camera obscura.[ten] : 8

The first permanent photo of a camera epitome was made in 1825 past Joseph Nicéphore Niépce using a sliding wooden box camera fabricated by Charles and Vincent Chevalier in Paris.[10] : 9–11 Niépce had been experimenting with means to set the images of a camera obscura since 1816. The photograph Niépce succeeded in creating shows the view from his window. It was fabricated using an 8-hour exposure on pewter coated with bitumen.[10] : ix Niépce called his process "heliography".[nine] : 5 Niépce corresponded with the inventor Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, and the pair entered into a partnership to improve the heliographic process. Niépce had experimented farther with other chemicals, to ameliorate contrast in his heliographs. Daguerre contributed an improved camera obscura design, but the partnership concluded when Niépce died in 1833.[10] : x Daguerre succeeded in developing a loftier-contrast and extremely sharp image past exposing on a plate coated with silver iodide, and exposing this plate again to mercury vapor.[9] : 6 Past 1837, he was able to ready the images with a mutual salt solution. He chosen this process Daguerreotype, and tried unsuccessfully for a couple of years to commercialize it. Somewhen, with help of the scientist and politician François Arago, the French government acquired Daguerre'due south process for public release. In commutation, pensions were provided to Daguerre as well as Niépce's son, Isidore.[x] : 11

In the 1830s, the English scientist William Henry Pull a fast one on Talbot independently invented a process to capture camera images using silver salts.[11] : 15 Although dismayed that Daguerre had beaten him to the declaration of photography, he submitted on January 31, 1839, a pamphlet to the Royal Institution entitled Some Business relationship of the Art of Photogenic Drawing, which was the first published description of photography. Within ii years, Talbot adult a two-footstep process for creating photographs on paper, which he called calotypes. The calotype process was the offset to utilize negative printing, which reverses all values in the reproduction process – black shows up every bit white and vice versa.[9] : 21 Negative press allows, in principle, an unlimited number of positive prints to be fabricated from the original negative.[xi] : sixteen The Calotype process as well introduced the ability for a printmaker to change the resulting prototype through retouching of the negative.[11] : 67 Calotypes were never as popular or widespread as daguerreotypes,[9] : 22 owing mainly to the fact that the latter produced sharper details.[12] : 370 Nevertheless, because daguerreotypes only produce a direct positive print, no duplicates tin can be fabricated. It is the two-footstep negative/positive process that formed the ground for modern photography.[ten] : 15

The Giroux daguerreotype photographic camera made by Maison Susse Frères in 1839, with a lens by Charles Chevalier, the first to be commercially produced[9] : 9

The first photographic camera adult for commercial manufacture was a daguerreotype camera, built by Alphonse Giroux in 1839. Giroux signed a contract with Daguerre and Isidore Niépce to produce the cameras in France,[ix] : 8–9 with each device and accessories costing 400 francs.[13] : 38 The camera was a double-box design, with a landscape lens fitted to the outer box, and a holder for a ground glass focusing screen and prototype plate on the inner box. By sliding the inner box, objects at various distances could be brought to as sharp a focus as desired. Subsequently a satisfactory prototype had been focused on the screen, the screen was replaced with a sensitized plate. A knurled cycle controlled a copper flap in forepart of the lens, which functioned every bit a shutter. The early on daguerreotype cameras required long exposure times, which in 1839 could be from 5 to 30 minutes.[9] [xiii] : 39

After the introduction of the Giroux daguerreotype camera, other manufacturers quickly produced improved variations. Charles Chevalier, who had before provided Niépce with lenses, created in 1841 a double-box camera using a one-half-sized plate for imaging. Chevalier's camera had a hinged bed, allowing for half of the bed to fold onto the back of the nested box. In add-on to having increased portability, the photographic camera had a faster lens, bringing exposure times downward to 3 minutes, and a prism at the front of the lens, which allowed the image to exist laterally correct.[xiv] : 6 Another French pattern emerged in 1841, created past Marc Antoine Gaudin. The Nouvel Appareil Gaudin camera had a metal disc with three differently-sized holes mounted on the front of the lens. Rotating to a different pigsty effectively provided variable f-stops, allowing different amounts of light into the camera.[15] : 28 Instead of using nested boxes to focus, the Gaudin camera used nested brass tubes.[14] : 7 In Germany, Peter Friedrich Voigtländer designed an all-metal camera with a conical shape that produced circular pictures of nearly 3 inches in diameter. The distinguishing characteristic of the Voigtländer camera was its employ of a lens designed by Joseph Petzval.[11] : 34 The f/three.5 Petzval lens was nearly 30 times faster than whatsoever other lens of the menstruation, and was the first to be made specifically for portraiture. Its design was the most widely used for portraits until Carl Zeiss introduced the anastigmat lens in 1889.[10] : 19

Within a decade of being introduced in America, 3 general forms of camera were in popular use: the American- or chamfered-box camera, the Robert's-type camera or "Boston box", and the Lewis-type camera. The American-box camera had beveled edges at the front and rear, and an opening in the rear where the formed image could be viewed on ground drinking glass. The top of the camera had hinged doors for placing photographic plates. Within there was i available slot for distant objects, and another slot in the back for close-ups. The lens was focused either by sliding or with a rack and pinion mechanism. The Robert's-type cameras were like to the American-box, except for having a knob-fronted worm gear on the front of the photographic camera, which moved the back box for focusing. Many Robert's-type cameras allowed focusing directly on the lens mount. The third popular daguerreotype photographic camera in America was the Lewis-type, introduced in 1851, which utilized a bellows for focusing. The primary trunk of the Lewis-type camera was mounted on the front box, just the rear section was slotted into the bed for easy sliding. One time focused, a gear up spiral was tightened to hold the rear section in place.[15] : 26–27 Having the bellows in the middle of the trunk facilitated making a 2d, in-camera copy of the original image.[14] : 17

Daguerreotype cameras formed images on silvered copper plates and images were only able to develop with mercury vapor.[16] The primeval daguerreotype cameras required several minutes to one-half an hour to expose images on the plates. By 1840, exposure times were reduced to only a few seconds owing to improvements in the chemical preparation and development processes, and to advances in lens pattern.[17] : 38 American daguerreotypists introduced manufactured plates in mass production, and plate sizes became internationally standardized: whole plate (vi.five x eight.five inches), 3-quarter plate (five.5 10 7 1/eight inches), half plate (4.5 x 5.5 inches), quarter plate (3.25 x iv.25 inches), sixth plate (2.75 x 3.25 inches), and ninth plate (two ten ii.five inches).[11] : 33–34 Plates were often cut to fit cases and jewelry with circular and oval shapes. Larger plates were produced, with sizes such as 9 x 13 inches ("double-whole" plate), or 13.v x 16.5 inches (Southworth & Hawes' plate).[15] : 25

The collodion moisture plate process that gradually replaced the daguerreotype during the 1850s required photographers to glaze and sensitize thin glass or iron plates soon earlier use and expose them in the camera while still moisture. Early on moisture plate cameras were very uncomplicated and little unlike from Daguerreotype cameras, just more than sophisticated designs eventually appeared. The Dubroni of 1864 allowed the sensitizing and developing of the plates to be carried out inside the camera itself rather than in a carve up darkroom. Other cameras were fitted with multiple lenses for photographing several small portraits on a unmarried larger plate, useful when making cartes de visite. It was during the moisture plate era that the employ of bellows for focusing became widespread, making the bulkier and less easily adjusted nested box blueprint obsolete.

For many years, exposure times were long enough that the photographer just removed the lens cap, counted off the number of seconds (or minutes) estimated to be required by the lighting weather condition, then replaced the cap. As more sensitive photographic materials became available, cameras began to comprise mechanical shutter mechanisms that immune very short and accurately timed exposures to be fabricated.

The use of photographic film was pioneered by George Eastman, who started manufacturing paper film in 1885 before switching to celluloid in 1889. His first photographic camera, which he chosen the "Kodak," was start offered for auction in 1888. Information technology was a very simple box camera with a stock-still-focus lens and single shutter speed, which along with its relatively low toll appealed to the average consumer. The Kodak came pre-loaded with plenty moving picture for 100 exposures and needed to exist sent back to the mill for processing and reloading when the scroll was finished. By the end of the 19th century Eastman had expanded his lineup to several models including both box and folding cameras.

Films as well made possible capture of motility (cinematography) establishing the film industry by the end of the 19th century.

Early fixed images [edit]

The commencement partially successful photograph of a camera image was fabricated in approximately 1816 by Nicéphore Niépce,[18] [19] using a very minor camera of his own making and a piece of newspaper coated with silver chloride, which darkened where it was exposed to light. No ways of removing the remaining unaffected silver chloride was known to Niépce, so the photograph was not permanent, somewhen becoming entirely darkened by the overall exposure to calorie-free necessary for viewing it. In the mid-1820s, Niépce used a sliding wooden box photographic camera made by Parisian opticians Charles and Vincent Chevalier, to experiment with photography on surfaces thinly coated with Bitumen of Judea.[20] The bitumen slowly hardened in the brightest areas of the paradigm. The unhardened bitumen was then dissolved abroad. One of those photographs has survived.

Daguerreotypes and calotypes [edit]

Afterward Niépce's death in 1830, his partner Louis Daguerre continued to experiment and by 1837 had created the kickoff practical photographic process, which he named the daguerreotype and publicly unveiled in 1839.[21] Daguerre treated a silver-plated canvass of copper with iodine vapor to give it a coating of low-cal-sensitive silver iodide. Later exposure in the camera, the epitome was developed by mercury vapor and fixed with a potent solution of ordinary salt (sodium chloride). Henry Fox Talbot perfected a different process, the calotype, in 1840. As commercialized, both processes used very elementary cameras consisting of two nested boxes. The rear box had a removable ground drinking glass screen and could slide in and out to conform the focus. After focusing, the ground glass was replaced with a lite-tight holder containing the sensitized plate or paper and the lens was capped. And then the lensman opened the front cover of the holder, uncapped the lens, and counted off every bit many minutes as the lighting atmospheric condition seemed to require before replacing the cap and closing the holder. Despite this mechanical simplicity, high-quality achromatic lenses were standard.[22]

Late 19th-century studio camera

Dry out plates [edit]

Collodion dry plates had been available since 1857, thanks to the work of Désiré van Monckhoven, but information technology was non until the invention of the gelatin dry plate in 1871 past Richard Leach Maddox that the moisture plate process could be rivaled in quality and speed. The 1878 discovery that heat-ripening a gelatin emulsion greatly increased its sensitivity finally made and then-chosen "instantaneous" snapshot exposures practical. For the beginning time, a tripod or other back up was no longer an accented necessity. With daylight and a fast plate or picture, a pocket-size camera could exist hand-held while taking the picture. The ranks of amateur photographers swelled and informal "candid" portraits became popular. There was a proliferation of photographic camera designs, from single- and twin-lens reflexes to large and bulky field cameras, simple box cameras, and even "detective cameras" bearded as pocket watches, hats, or other objects.

The brusk exposure times that fabricated candid photography possible besides necessitated some other innovation, the mechanical shutter. The very first shutters were separate accessories, though built-in shutters were mutual by the end of the 19th century.[22]

Invention of photographic flick [edit]

Kodak No. two Credibility box camera, circa 1920

The use of photographic movie was pioneered by George Eastman, who started manufacturing paper flick in 1885 before switching to celluloid in 1888–1889. His commencement camera, which he called the "Kodak", was showtime offered for auction in 1888. Information technology was a very simple box camera with a fixed-focus lens and unmarried shutter speed, which along with its relatively low price appealed to the average consumer. The Kodak came pre-loaded with enough film for 100 exposures and needed to be sent back to the factory for processing and reloading when the roll was finished. Past the terminate of the 19th century Eastman had expanded his lineup to several models including both box and folding cameras.

In 1900, Eastman took mass-market photography one stride farther with the Brownie, a simple and very inexpensive box camera that introduced the concept of the snapshot. The Brownie was extremely popular and various models remained on auction until the 1960s.

Film besides immune the pic camera to develop from an expensive toy to a practical commercial tool.

Despite the advances in low-price photography made possible by Eastman, plate cameras still offered college-quality prints and remained popular well into the 20th century. To compete with rollfilm cameras, which offered a larger number of exposures per loading, many inexpensive plate cameras from this era were equipped with magazines to hold several plates at once. Special backs for plate cameras assuasive them to use film packs or rollfilm were as well available, every bit were backs that enabled rollfilm cameras to use plates.

Except for a few special types such as Schmidt cameras, most professional astrographs continued to use plates until the finish of the 20th century when electronic photography replaced them.

35 mm [edit]

A number of manufacturers started to use 35 mm film for still photography between 1905 and 1913. The first 35 mm cameras available to the public, and reaching significant numbers in sales were the Tourist Multiple, in 1913, and the Simplex, in 1914.[ commendation needed ]

Oskar Barnack, who was in charge of research and development at Leitz, decided to investigate using 35 mm cine motion picture for still cameras while attempting to build a compact camera capable of making high-quality enlargements. He built his epitome 35 mm photographic camera (Ur-Leica) around 1913, though further development was delayed for several years by World War I. It wasn't until after Earth State of war I that Leica commercialized their starting time 35 mm cameras. Leitz examination-marketed the design betwixt 1923 and 1924, receiving enough positive feedback that the photographic camera was put into production as the Leica I (for Leitz camera) in 1925. The Leica'south immediate popularity spawned a number of competitors, almost notably the Contax (introduced in 1932), and cemented the position of 35 mm every bit the format of option for high-finish compact cameras.

Kodak got into the marketplace with the Retina I in 1934, which introduced the 135 cartridge used in all modern 35 mm cameras. Although the Retina was insufficiently inexpensive, 35 mm cameras were nevertheless out of attain for most people and rollfilm remained the format of choice for mass-market cameras. This changed in 1936 with the introduction of the inexpensive Argus A and to an fifty-fifty greater extent in 1939 with the arrival of the immensely popular Argus C3. Although the cheapest cameras notwithstanding used rollfilm, 35 mm film had come to boss the market by the time the C3 was discontinued in 1966.

The fledgling Japanese camera industry began to take off in 1936 with the Catechism 35 mm rangefinder, an improved version of the 1933 Kwanon image. Japanese cameras would begin to become popular in the West after Korean War veterans and soldiers stationed in Nihon brought them back to the Us and elsewhere.

TLRs and SLRs [edit]

The get-go practical reflex camera was the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex medium format TLR of 1928. Though both unmarried- and twin-lens reflex cameras had been bachelor for decades, they were likewise bulky to achieve much popularity. The Rolleiflex, notwithstanding, was sufficiently meaty to attain widespread popularity and the medium-format TLR design became popular for both loftier- and depression-finish cameras.

A similar revolution in SLR design began in 1933 with the introduction of the Ihagee Exakta, a compact SLR which used 127 rollfilm. This was followed three years later by the first Western SLR to utilise 135 film, the Kine Exakta (World's first truthful 35mm SLR was Soviet "Sport" camera, marketed several months before Kine Exakta, though "Sport" used its ain pic cartridge). The 35mm SLR design gained immediate popularity and there was an explosion of new models and innovative features afterwards World War II. In that location were as well a few 35 mm TLRs, the best-known of which was the Contaflex of 1935, only for the most role these met with trivial success.

The first major post-war SLR innovation was the center-level viewfinder, which first appeared on the Hungarian Duflex in 1947 and was refined in 1948 with the Contax Southward, the first photographic camera to use a pentaprism. Prior to this, all SLRs were equipped with waist-level focusing screens. The Duflex was also the first SLR with an instant-return mirror, which prevented the viewfinder from being blacked out after each exposure. This aforementioned time period also saw the introduction of the Hasselblad 1600F, which set the standard for medium format SLRs for decades.

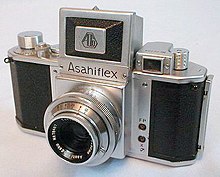

In 1952 the Asahi Optical Visitor (which later became well known for its Pentax cameras) introduced the commencement Japanese SLR using 135 motion picture, the Asahiflex. Several other Japanese camera makers also entered the SLR marketplace in the 1950s, including Catechism, Yashica, and Nikon. Nikon's entry, the Nikon F, had a full line of interchangeable components and accessories and is generally regarded as the first Japanese system camera. It was the F, along with the before S series of rangefinder cameras, that helped found Nikon'southward reputation as a maker of professional-quality equipment and one of the world'south best known brands.

Instant cameras [edit]

While conventional cameras were becoming more refined and sophisticated, an entirely new type of camera appeared on the market in 1948. This was the Polaroid Model 95, the earth'due south commencement viable instant-picture photographic camera. Known every bit a Land Camera after its inventor, Edwin Country, the Model 95 used a patented chemic process to produce finished positive prints from the exposed negatives in under a minute. The Land Camera caught on despite its relatively high price and the Polaroid lineup had expanded to dozens of models by the 1960s. The beginning Polaroid camera aimed at the popular market, the Model 20 Swinger of 1965, was a huge success and remains 1 of the tiptop-selling cameras of all time.

Automation [edit]

The first camera to feature automatic exposure was the selenium low-cal meter-equipped, fully automatic Super Kodak Six-20 pack of 1938, only its extremely high toll (for the time) of $225 (equivalent to $iv,137 in 2020)[23] kept it from achieving any caste of success. By the 1960s, however, low-cost electronic components were commonplace and cameras equipped with light meters and automatic exposure systems became increasingly widespread.

The side by side technological advance came in 1960, when the German language Mec 16 SB subminiature became the first camera to place the light meter backside the lens for more than accurate metering. However, through-the-lens metering ultimately became a characteristic more commonly constitute on SLRs than other types of photographic camera; the showtime SLR equipped with a TTL arrangement was the Topcon RE Super of 1962.

Digital cameras [edit]

Digital cameras differ from their analog predecessors primarily in that they do non utilise film, simply capture and save photographs on digital memory cards or internal storage instead. Their depression operating costs accept relegated chemical cameras to niche markets. Digital cameras now include wireless advice capabilities (for example Wi-Fi or Bluetooth) to transfer, print, or share photos, and are commonly constitute on mobile phones.

Digital imaging technology [edit]

The first semiconductor image sensor was the CCD, invented by Willard S. Boyle and George E. Smith at Bell Labs in 1969.[24] While researching MOS applied science, they realized that an electric charge was the analogy of the magnetic bubble and that it could be stored on a tiny MOS capacitor. As it was fairly straightforward to fabricate a serial of MOS capacitors in a row, they connected a suitable voltage to them so that the charge could be stepped forth from ane to the next.[25] The CCD is a semiconductor circuit that was afterwards used in the commencement digital video cameras for telly broadcasting.[26]

The NMOS active-pixel sensor (APS) was invented by Olympus in Japan during the mid-1980s. This was enabled by advances in MOS semiconductor device fabrication, with MOSFET scaling reaching smaller micron and then sub-micron levels.[27] [28] The NMOS APS was fabricated past Tsutomu Nakamura'due south team at Olympus in 1985.[29] The CMOS active-pixel sensor (CMOS sensor) was after developed by Eric Fossum's team at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1993.[30] [27]

Early digital camera prototypes [edit]

The concept of digitizing images on scanners, and the concept of digitizing video signals, predate the concept of making still pictures by digitizing signals from an array of discrete sensor elements. Early on spy satellites used the extremely complex and expensive method of de-orbit and airborne retrieval of moving-picture show canisters. Engineering science was pushed to skip these steps through the use of in-satellite developing and electronic scanning of the flick for direct transmission to the ground. The amount of moving-picture show was even so a major limitation, and this was overcome and greatly simplified by the push to develop an electronic image capturing array that could be used instead of flick. The first electronic imaging satellite was the KH-11 launched past the NRO in late 1976. Information technology had a accuse-coupled device (CCD) array with a resolution of 800 x 800 pixels (0.64 megapixels).[31] At Philips Labs in New York, Edward Stupp, Pieter Cath and Zsolt Szilagyi filed for a patent on "All Solid Country Radiations Imagers" on six September 1968 and constructed a apartment-screen target for receiving and storing an optical image on a matrix composed of an array of photodiodes connected to a capacitor to form an array of two terminal devices continued in rows and columns. Their U.s. patent was granted on 10 Nov 1970.[32] Texas Instruments engineer Willis Adcock designed a filmless camera that was not digital and applied for a patent in 1972, but information technology is not known whether it was e'er congenital.[33]

The Cromemco Cyclops, introduced every bit a hobbyist construction projection in 1975,[34] was the outset digital camera to be interfaced to a microcomputer. Its image sensor was a modified metallic-oxide-semiconductor (MOS) dynamic RAM (DRAM) memory chip.[35]

The first recorded attempt at building a self-contained digital photographic camera was in 1975 by Steven Sasson, an engineer at Eastman Kodak.[36] [37] Information technology used the so-new solid-state CCD image sensor chips developed past Fairchild Semiconductor in 1973.[38] The camera weighed 8 pounds (3.6 kg), recorded black-and-white images to a compact cassette tape, had a resolution of 0.01 megapixels (x,000 pixels), and took 23 seconds to capture its commencement epitome in December 1975. The prototype camera was a technical exercise, not intended for production.

Analog electronic cameras [edit]

Handheld electronic cameras, in the sense of a device meant to be carried and used as a handheld film camera, appeared in 1981 with the demonstration of the Sony Mavica (Magnetic Video Photographic camera). This is non to exist confused with the later cameras by Sony that besides bore the Mavica name. This was an analog camera, in that it recorded pixel signals continuously, as videotape machines did, without converting them to discrete levels; information technology recorded television-similar signals to a 2 × 2 inch "video floppy".[39] In essence, it was a video moving picture camera that recorded single frames, 50 per deejay in field mode, and 25 per disk in frame mode. The paradigm quality was considered equal to that of then-current televisions.

Analog electronic cameras practice not announced to have reached the market until 1986 with the Canon RC-701. Canon demonstrated a prototype of this model at the 1984 Summertime Olympics, press the images in the Yomiuri Shinbun, a Japanese paper. In the Us, the first publication to employ these cameras for real reportage was U.s. Today, in its coverage of Earth Series baseball. Several factors held back the widespread adoption of analog cameras; the cost (upwards of $twenty,000, equivalent to $47,000 in 2020[23]), poor image quality compared to picture show, and the lack of quality affordable printers. Capturing and printing an image originally required admission to equipment such as a frame grabber, which was beyond the reach of the average consumer. The "video floppy" disks later had several reader devices available for viewing on a screen but were never standardized as a reckoner drive.

The early adopters tended to exist in the news media, where the price was negated by the utility and the ability to transmit images by telephone lines. The poor image quality was outset by the depression resolution of newspaper graphics. This capability to transmit images without a satellite link was useful during the 1989 Tiananmen Foursquare protests and the starting time Gulf War in 1991.

US regime agencies likewise took a strong interest in the still video concept, notably the U.s.a. Navy for use equally a existent-time air-to-bounding main surveillance organization.

The first analog electronic photographic camera marketed to consumers may take been the Casio VS-101 in 1987. A notable analog camera produced the same year was the Nikon QV-1000C, designed as a press camera and not offered for sale to full general users, which sold simply a few hundred units. It recorded images in greyscale, and the quality in paper print was equal to film cameras. In appearance it closely resembled a mod digital single-lens reflex camera. Images were stored on video floppy disks.

Silicon Pic, a proposed digital sensor cartridge for film cameras that would allow 35 mm cameras to accept digital photographs without modification was announced in belatedly 1998. Silicon Motion picture was to work as a ringlet of 35 mm moving-picture show, with a 1.3 megapixel sensor backside the lens and a battery and storage unit fitting in the motion picture holder in the camera. The product, which was never released, became increasingly obsolete due to improvements in digital camera technology and affordability. Silicon Films' parent company filed for bankruptcy in 2001.[40]

Early true digital cameras [edit]

Minolta RD-175, the first portable digital SLR camera, introduced by Minolta in 1995.

Past the late 1980s, the technology required to produce truly commercial digital cameras existed. The beginning true portable digital photographic camera that recorded images as a computerized file was likely the Fuji DS-1P of 1988, which recorded to a ii MB SRAM (static RAM) retention carte that used a battery to proceed the data in retentiveness. This photographic camera was never marketed to the public.

The first digital photographic camera of any kind always sold commercially was possibly the MegaVision Tessera in 1987[41] though there is not extensive documentation of its sale known. The showtime portable digital photographic camera that was actually marketed commercially was sold in December 1989 in Nihon, the DS-X by Fuji[42] The get-go commercially available portable digital photographic camera in the United states was the Dycam Model ane, commencement shipped in November 1990.[43] Information technology was originally a commercial failure because it was black-and-white, low in resolution, and price well-nigh $i,000 (equivalent to $ii,000 in 2020[23]).[44] It later saw modest success when it was re-sold as the Logitech Fotoman in 1992. It used a CCD image sensor, stored pictures digitally, and connected direct to a estimator for download.[45] [46] [47]

Digital SLRs (DSLRs) [edit]

Nikon was interested in digital photography since the mid-1980s. In 1986, while presenting to Photokina, Nikon introduced an operational image of the first SLR-type digital camera (Still Video Camera), manufactured by Panasonic.[48] The Nikon SVC was built effectually a sensor 2/three " charge-coupled device of 300,000 pixels. Storage media, a magnetic floppy inside the camera allows recording 25 or l B&Westward images, depending on the definition.[49] In 1988, Nikon released the outset commercial DSLR camera, the QV-1000C.[48]

In 1991, Kodak brought to market the Kodak DCS (Kodak Digital Camera System), the beginning of a long line of professional Kodak DCS SLR cameras that were based in part on film bodies, oftentimes Nikons. It used a i.3 megapixel sensor, had a beefy external digital storage system and was priced at $13,000 (equivalent to $25,000 in 2020[23]). At the inflow of the Kodak DCS-200, the Kodak DCS was dubbed Kodak DCS-100.

The move to digital formats was helped by the formation of the get-go JPEG and MPEG standards in 1988, which allowed epitome and video files to exist compressed for storage. The first consumer camera with a liquid crystal brandish on the dorsum was the Casio QV-10 developed by a squad led by Hiroyuki Suetaka in 1995. The first camera to use CompactFlash was the Kodak DC-25 in 1996.[50] The beginning camera that offered the power to record video clips may have been the Ricoh RDC-1 in 1995.

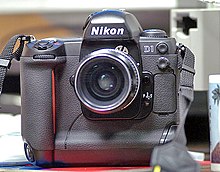

In 1995 Minolta introduced the RD-175, which was based on the Minolta 500si SLR with a splitter and 3 independent CCDs. This combination delivered 1.75M pixels. The benefit of using an SLR base was the ability to use any existing Minolta AF mount lens. 1999 saw the introduction of the Nikon D1, a 2.74 megapixel camera that was the starting time digital SLR developed entirely from the ground up past a major manufacturer, and at a cost of under $6,000 (equivalent to $10,200 in 2020[23]) at introduction was affordable by professional photographers and high-end consumers. This photographic camera also used Nikon F-mount lenses, which meant picture photographers could use many of the same lenses they already endemic.

Digital camera sales continued to flourish, driven by technology advances. The digital market segmented into unlike categories, Compact Digital Withal Cameras, Bridge Cameras, Mirrorless Compacts and Digital SLRs.

Since 2003, digital cameras accept outsold pic cameras[51] and Kodak appear in January 2004 that they would no longer sell Kodak-branded moving picture cameras in the adult earth[52] – and in 2012 filed for defalcation subsequently struggling to adjust to the changing manufacture.[53]

Camera phones [edit]

The first commercial camera phone was the Kyocera Visual Telephone VP-210, released in Japan in May 1999.[54] It was called a "mobile videophone" at the time,[55] and had a 110,000-pixel forepart-facing camera.[54] It stored up to 20 JPEG digital images, which could be sent over electronic mail, or the phone could transport upward to two images per second over Japan'due south Personal Handy-phone System (PHS) cellular network.[54] The Samsung SCH-V200, released in South Korea in June 2000, was also i of the first phones with a built-in camera. It had a TFT liquid-crystal brandish (LCD) and stored upwards to 20 digital photos at 350,000-pixel resolution. Still, it could not send the resulting image over the telephone role, but required a figurer connection to access photos.[56] The first mass-market camera phone was the J-SH04, a Abrupt J-Phone model sold in Japan in November 2000.[57] [56] It could instantly transmit pictures via cell phone telecommunications.[58]

Ane of the major engineering science advances was the development of CMOS sensors, which helped drive sensor costs low enough to enable the widespread adoption of camera phones. Smartphones at present routinely include high resolution digital cameras.

See also [edit]

- History of photography

- Photographic lens pattern

- Movie camera

References [edit]

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Larry D.; Francis, Gregory Eastward. (2007). "Light". Physics: A World View (half dozen ed.). Belmont, California: Thomson Brooks/Cole. p. 339. ISBN978-0-495-01088-iii.

- ^ a b Plott, John C. (1984). Global History of Philosophy: The Period of scholasticism (part one). p. 460. ISBN978-0-89581-678-viii.

- ^ a b Belbachir, Ahmed Nabil (2010). Smart Cameras. Springer Scientific discipline & Business Media. ISBN978-i-4419-0953-4.

The invention of the camera can be traced back to the tenth century when the Arab scientist Al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham alias Alhacen provided the first articulate description and correct assay of the (human) vision procedure. Although the effects of single light passing through the pinhole have already been described by the Chinese Mozi (Lat. Micius) (5th century B), the Greek Aristotle (fourth century BC), and the Arab

- ^ Plott, John C. (1984). Global History of Philosophy: The Period of scholasticism (part ane). p. 460. ISBN978-0-89581-678-8.

According to Nazir Ahmed if just Ibn-Haitham's fellow-workers and students had been as alert as he, they might even take invented the art of photography since al-Haytham's experiments with convex and concave mirrors and his invention of the "pinhole camera" whereby the inverted paradigm of a candle-flame is projected were amongst his many successes in experimentation. I might likewise nearly claim that he had anticipated much that the nineteenth century Fechner did in experimentation with after-images.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas J.; Finger, Stanley (2001), "The eye every bit an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective", Perception, xxx (10): 1157–1177, doi:10.1068/p3210, PMID 11721819, S2CID 8185797,

The principles of the camera obscura first began to be correctly analysed in the eleventh century, when they were outlined by Ibn al-Haytham.

- ^ Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in Communist china, vol. IV, part 1: Physics and Concrete Engineering (PDF). p. 98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

Alhazen used the camera obscura especially for observing solar eclipses, as indeed Aristotle is said to have done, and information technology seems that, like Shen Kua, he had predecessors in its report, since he did not claim it every bit any new finding of his ain. But his treatment of it was competently geometrical and quantitative for the first time.

- ^ "Who Invented Camera Obscura?". Photography History Facts.

All these scientists experimented with a small hole and calorie-free simply none of them suggested that a screen is used so an image from one side of a hole on the surface could be projected at the screen on the other. Showtime, one to do and so was Alhazen (also known as Ibn al-Haytham) in 11th century.

- ^ Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in China, vol. IV, office 1: Physics and Concrete Technology (PDF). p. 99. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2017. Retrieved five September 2016.

The genius of Shen Kua'due south insight into the relation of focal point and pinhole can better be appreciated when we read in Vocaliser that this was offset understood in Europe by Leonardo da Vinci (+ 1452 to + 1519), almost v hundred years later. A diagram showing the relation occurs in the Codice Atlantico, Leonardo thought that the lens of the eye reversed the pinhole effect, so that the image did not announced inverted on the retina; though in fact, it does. Really, the analogy of focal-betoken and pivot-betoken must take been understood by Ibn al-Haitham, who died simply about the fourth dimension when Shen Ku was born.

- ^ a b c d e f chiliad h i j Gustavson, Todd (2009). Camera: a history of photography from daguerreotype to digital. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN978-1-4027-5656-6.

- ^ a b c d e f chiliad h i Gernsheim, Helmut (1986). A Concise History of Photography (iii ed.). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN978-0-486-25128-8.

- ^ a b c d e Hirsch, Robert (2000). Seizing the Light: A History of Photography. New York: McGraw-Loma Companies, Inc. ISBN978-0-697-14361-7.

- ^ London, Barbara; Upton, John; Kobré, Kenneth; Brill, Betsy (2002). Photography (7 ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN978-0-13-028271-2.

- ^ a b Frizot, Michel (January 1998). "Light machines: On the threshold of invention". In Michel Frizot (ed.). A New History of Photography. Koln, Frg: Konemann. ISBN978-3-8290-1328-four.

- ^ a b c Gustavson, Todd (one November 2011). 500 Cameras: 170 Years of Photographic Innovation. Toronto, Ontario: Sterling Publishing, Inc. ISBN978-1-4027-8086-eight.

- ^ a b c Spira, S.F.; Lothrop, Jr., Easton Due south.; Spira, Jonathan B. (2001). The History of Photography as Seen Through the Spira Drove. New York: Aperture. ISBN978-0-89381-953-8.

- ^ "Daguerreotype". Scientific American. ii (38): 302. 1847. doi:x.1038/scientificamerican06121847-302e. ISSN 0036-8733. JSTOR 24924116.

- ^ Starl, Timm (January 1998). "A New Globe of Pictures: The Daguerreotype". In Michel Frizot (ed.). A New History of Photography. Koln, Frg: Konemann. ISBN978-3-8290-1328-4.

- ^ Newhall, Beaumont (1982). The History of Photography. New York, New York: The Museum of Modernistic Fine art. p. 13. ISBN0-87070-381-one.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, of exposure to low-cal. Although the simply example of his camera work that remains today appears to take been made in 1826, his letters go out no doubt that he had succeeded in fixing the camera's image a decade earlier.

- ^ Leslie Stroebel and Richard D. Zakia (1993). The Focal encyclopedia of photography (3rd ed.). Focal Printing. p. 6. ISBN978-0-240-51417-8.

- ^ Davenport, Alma (1999). The history of photography: an overview. Albuquerque, NM: Academy of New United mexican states Press. p. half-dozen. ISBN0-8263-2076-7.

- ^ Kosinski Dorothy, The Artist and the Camera, Degas to Picasso. New Haven: Yale University Printing,1999. p.25

- ^ a b Wade, John (1979). A Short History of the Camera. Watford: Fountain Press. ISBN0-85242-640-2.

- ^ a b c d e 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the Usa: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Utilize as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economic system of the United states of america (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Banking company of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved ane Jan 2020.

- ^ James R. Janesick (2001). Scientific charge-coupled devices. SPIE Press. pp. three–4. ISBN978-0-8194-3698-6.

- ^ Williams, J. B. (2017). The Electronics Revolution: Inventing the Hereafter. Springer. pp. 245–viii. ISBN9783319490885.

- ^ Boyle, William Southward; Smith, George E. (1970). "Charge Coupled Semiconductor Devices". Bell Syst. Tech. J. 49 (4): 587–593. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1970.tb01790.x.

- ^ a b Fossum, Eric R. (12 July 1993). Blouke, Morley M. (ed.). "Active pixel sensors: are CCDs dinosaurs?". SPIE Proceedings Vol. 1900: Accuse-Coupled Devices and Solid State Optical Sensors Iii. International Social club for Eyes and Photonics. 1900: two–14. Bibcode:1993SPIE.1900....2F. CiteSeerX10.i.ane.408.6558. doi:10.1117/12.148585. S2CID 10556755.

- ^ Fossum, Eric R. (2007). "Active Pixel Sensors" (PDF). Semantic Scholar. S2CID 18831792. Archived from the original (PDF) on ix March 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ Matsumoto, Kazuya; et al. (1985). "A new MOS phototransistor operating in a not-destructive readout mode". Japanese Periodical of Applied Physics. 24 (5A): L323. Bibcode:1985JaJAP..24L.323M. doi:x.1143/JJAP.24.L323.

- ^ Fossum, Eric R.; Hondongwa, D. B. (2014). "A Review of the Pinned Photodiode for CCD and CMOS Paradigm Sensors". IEEE Journal of the Electron Devices Society. 2 (3): 33–43. doi:10.1109/JEDS.2014.2306412.

- ^ globalsecurity.org – KH-11 KENNAN, 24 April 2007

- ^ United states 3540011

- ^ U.s.a. 4057830 and US 4163256 were filed in 1972 but were only afterward awarded in 1976 and 1977. "1970s". Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ Walker, Terry; Garland, Harry; Melen, Roger (February 1975). "Build Cyclops". Popular Electronics. Ziff Davis. 7 (two): 27–31.

- ^ Benchoff, Brian (17 April 2016). "Building the First Digital Camera". Hackaday . Retrieved xxx April 2016.

the Cyclops was the get-go digital camera

- ^ "Digital Photography Milestones from Kodak". Women in Photography International . Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ^ "Kodak weblog: We Had No Thought". Archived from the original on 29 May 2010.

- ^ Michael R. Peres (2007). The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography (4th ed.). Focal Printing. ISBN978-0-240-80740-9.

- ^ Kenji Toyoda (2006). "Digital Still Cameras at a Glance". In Junichi Nakamura (ed.). Image sensors and signal processing for digital yet cameras. CRC Press. p. 5. ISBN978-0-8493-3545-7.

- ^ Askey, Phil (2001). "Silicon Film – vaporized-ware". Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ^ "MegaVision Professional Photographic camera Backs".

- ^ History of the digital camera and digital imaging

- ^ "Digital cameras, the next wave. (Electronic Imaging Issue; includes related articles) | HighBeam Business: Make it Prepared". Archived from the original on 3 May 2014.

- ^ Inc, InfoWorld Media Group (12 Baronial 1991). "InfoWorld". InfoWorld Media Group, Inc. – via Google Books.

- ^ "History of the digital camera and digital imaging". The Digital Camera Museum.

- ^ "Dycam Model 1: The world's first consumer digital still photographic camera". DigiBarn computer museum.

- ^ Carolyn Said, "DYCAM Model 1: The commencement portable Digital Nevertheless Camera", MacWeek, vol. 4, No. 35, 16 Oct. 1990, p. 34.

- ^ a b David D. Busch (2011), Nikon D70 Digital Field Guide, page 11, John Wiley & Sons

- ^ Nikon SLR-type digital cameras, Pierre Jarleton

- ^ "Kodak DC25 (1996)". DigitalKamera Museum.

- ^ "Digital outsells film, but film notwithstanding king to some". Macworld. 23 September 2004.

- ^ Smith, Tony (20 January 2004). "Kodak to driblet 35 mm cameras in Europe, United states". The Register. Retrieved 3 Apr 2007.

- ^ "Eastman Kodak Files for Bankruptcy". The New York Times. 19 January 2012.

- ^ a b c "Camera phones: A look back and forward". Computerworld. xi May 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "First mobile videophone introduced". CNN. xviii May 1999. Retrieved fifteen September 2019.

- ^ a b "From J-Phone to Lumia 1020: A complete history of the camera telephone". Digital Trends. 11 Baronial 2013. Retrieved xv September 2019.

- ^ "Evolution of the Camera phone: From Sharp J-SH04 to Nokia 808 Pureview". Hoista.net. 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "Taking pictures with your telephone". BBC News. BBC. 18 September 2001. Retrieved xv September 2019.

External links [edit]

- [one] The Digital Photographic camera Museum, with history section

- [2] The Definitive Complete History of the Camera

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_camera

Posted by: higginbothamfacking.blogspot.com

0 Response to "When Was The Camera Made"

Post a Comment